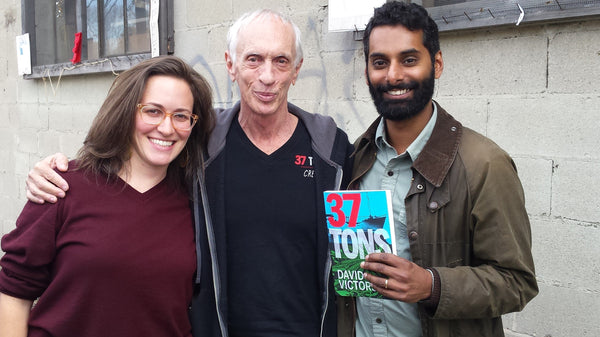

For David Victorson, a job involving cannabis is nothing new. The 67-year-old social activist and speaker recently found himself in Miami on business, working with the local community to open a dispensary. But Victorson's got more knowledge of the plant than many looking to join the country's legal cannabis boom. In 1978, he bewildered authorities when he was caught smuggling what was then the largest shipment of cannabis—a staggering 37 tons—into the United States off the coast of Seattle.

"In my day, the statue for marijuana didn't include multi-ton loads. They didn't know anything about it!" Victorson tells me over the phone in a thick Boston accent. "They were very angry to find out that I'd been running 50 tons of pot each year from Colombia to the United States for eight years." In his memoir, 37 Tons, Victorson recounts what led him onto that fated freighter, but be warned: He's not one to regale his readers with tall tales of cartel glory. Instead, his writing is unyielding and raw, as he navigates his life from poverty to career smuggling and out of harrowing addiction.

Like most dealers, Victorson began small. He sold in and around Dorchester—the rough, dog-eat-dog Boston neighborhood he called home—quickly outgrowing the local scene for in favor of smuggling hash out of Amsterdam, India, and Nepal. With a disposition for circumventing the law, Victorson quickly appeared on the radar of the Colombian cannabis cartel. Before long, he was importing the drug into the US en masse and netting himself a cool $30 million, with a lifestyle to match.

However, Victorson's narrative is a far cry from the greed popularized through the media's portrayal of drug trafficking. Through his heydey as a smuggler and the aftermath—which included three months of jail time in a Bolivian military prison and four years locked up in Lompoc Federal Prison off the California coast—Victorson is marked by his giving spirit. "The way I was raised set me up to be a hostile person who didn't trust or believe in anybody I believe that most kids who are born into poverty will always have that," he says. "I'm a hard person to accept love—I don't believe it and I don't trust people. What I can do to soften myself up is give to other people. I believe that's a big part of growing up and being part of the world." 37 Tons finds the former smuggler grappling with the conflicting moral codes of society at large and those of the drug world, and it's this struggle that makes for a fascinating and high-speed read about survival.

I spoke to Victorson about his new life, his childhood, and his "good run."

VICE: How it feels to be working again with cannabis again, even though it's in a considerably different way?

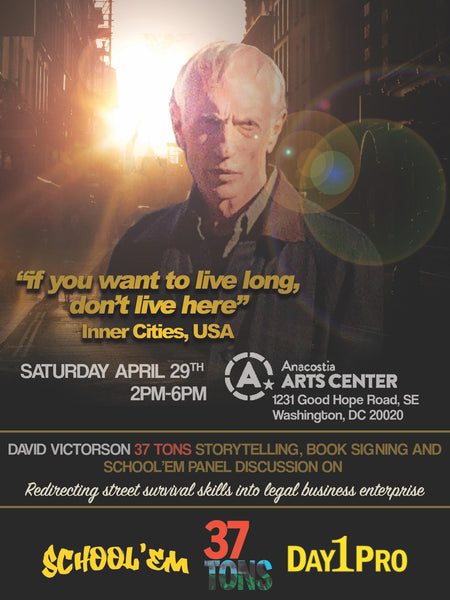

David Victorson: It's hilarious! When I got busted in 1978, there were 5,000 people protesting my arrest. Even back then, people knew marijuana was a much better recreational substance than alcohol. Now, I'm invited to speak at a cannabis event in Washington DC I know people want to hear pirate stories about the outrageous behavior and high-risk adventure, but I want to use the platform to talk about cannabis as an emerging industry. We don't have to end up looking like alcohol and tobacco. We can end up employing—and with good salaries—marginalized people, people without college education, and people who have a hard time making it in the world.

As well as people who have been historically involved with the selling of cannabis and have gone to jail for it.

Exactly. I never held any animosity over the fact that I went to jail for 37 tons of pot, because I had been smuggling since I was 16. I made over $30 million and had a phenomenal life. I was treated like a rock star everywhere I went. I had a good run.

Thirty-seven tons must have been a massive shock to the authorities.

We were generating over $2 billion and they had no idea I existed. I had so many identities, passports, and cover stories that when I was busted they couldn't figure out who I was.

As a person who was constantly making up new identities, did you ever get to a point where you were having fun with it? How did you choose your characters?

Being that guy was my craft. It was like an actor studying for a play. You have ideas for a backstory, all the necessary documents, and a script—and you have to look the right part. I taught myself how to perfect it. It was never a spur-of-the-moment thing; it was something that was done so I didn't get caught and the people I cared about weren't jeopardized.

Throughout 37 Tons, you lament that the smuggling life meant forfeiting a lot of interpersonal relationships. Why were you set on leading an outsider's life?

It's a question I think about now when I work with street kids. When I was growing up, I went to school hungry every day and in class learned about things that wouldn't make me money so I could eat. [Learning] didn't matter to me because I was spending my school day planning how I would get food. I had no safety net—if I didn't earn, I was going to be hungry. Even when I was in community college, I was smuggling hash because I needed something to fall back on if it didn't work out. Most kids have parents or a community, but I never had that. The only thing I knew in my heart was that I had to take care of myself no matter what, because no one else could be counted on to do that.

Another recurring motif in 37 Tons is fixated on "codes."

People talk about having a moral compass or value system. I read a lot of Adam Smith, and he talks about the difference between civil law and natural law. Civil law was created by people in power to keep them in power, while natural law is the instinctive difference between right and wrong. Even though I led a hard life, I always felt like I did what felt right in my heart. I don't agree with the silent contract we have with society. I believe in natural law—the law of the street. You're taught right from wrong—if you're lucky—otherwise the street would teach it to you.

In the smuggling industry, you couldn't be a liar. If you were, you'd cause people to go to jail or be killed. You couldn't be a thief, because if you stole, other people would suffer for your crime. Loyalty to the people who work with you is a huge deal. There were over 200 people involved in the entire smuggling process, but only two of us went to prison for it. We kept our mouths shut because that's what you do. Meanwhile, people in the corporate world lie, cheat, and steal all the time so they can move up the corporate ladder. I had the most honest and straightforward relationships with everyone I worked with in Colombia, Nepal, and India.

Even though the cannabis industry is rapidly growing, there's still a massive issue with smuggling. What are your thoughts on this?

I don't find it good on any level that young people are risking their freedom to make a profit from smuggling cannabis. I'd rather they'd wait until there's enough room in the industry for them to fit in legally. There's going to be good job opportunities in the industry—the average worker is making approximately $50,000 a year and I'm pretty sure what each state is going to do is say that you can't have a felony conviction within the last seven years. So if you do something stupid like transport weed over state lines and get caught, you're getting a felony conviction. That means you're dead to this industry. It's really important to me that people stay patient and not get greedy or ambitious to the point that they end up in prison.

How do you feel when people romanticize the life of a smuggler?

It's just a fantasy. They have no idea the tension that exists—the loneliness, pain, regret. You walk around and see women pushing strollers and kids eating ice cream and you know that's not going to be part of your life. People want to put you in prison. It's not a relaxing adventure.

You've recently hit 34 years of sobriety. What led you to your rock bottom?

I was at a point where the DEA, the FBI, Interpol, and international agencies people haven't even heard of were after me. I knew I couldn't go back to smuggling and I had to find something new to do. I never had another job, and no concept of what a normal life would be like. I was finally acknowledging the pain I went through. When I got busted and knew I was going to lose everything, I started snorting heroin and coke and drinking. I did it all alone and one day I woke up in a closet in my house totally naked, unshowered, and covered in fleas. I felt like a snake was eating me from the inside. Sobriety is the basis of my lifestyle because I know if I drink or do drugs, my life will fall apart.

You started School 'Em last year, a program geared toward at-risk inner-city youth. What do you try to hit when you're speaking to a young audience about your life?

I try to hit an emotional connection with them. I don't want them just to listen, I want them to feel what I'm talking about. At the end of the day, it's about how I can stop kids growing up in poverty from taking the path I took. I work with a lot of kids who are drug dealers now and I teach them that if you substitute another commodity for drugs, you have the skills to run a business. We're just going to teach you what white people know and you weren't taught. The only different to me between a drug dealer and a banker is a suit.